Umami, often called the “fifth taste”, is more than just a flavor—it is a pillar of Japanese cuisine. While sweetness, sourness, saltiness, and bitterness are recognized worldwide, umami offers a unique depth that has shaped Japan’s culinary traditions and is now embraced globally.

The Basic Definition of Umami

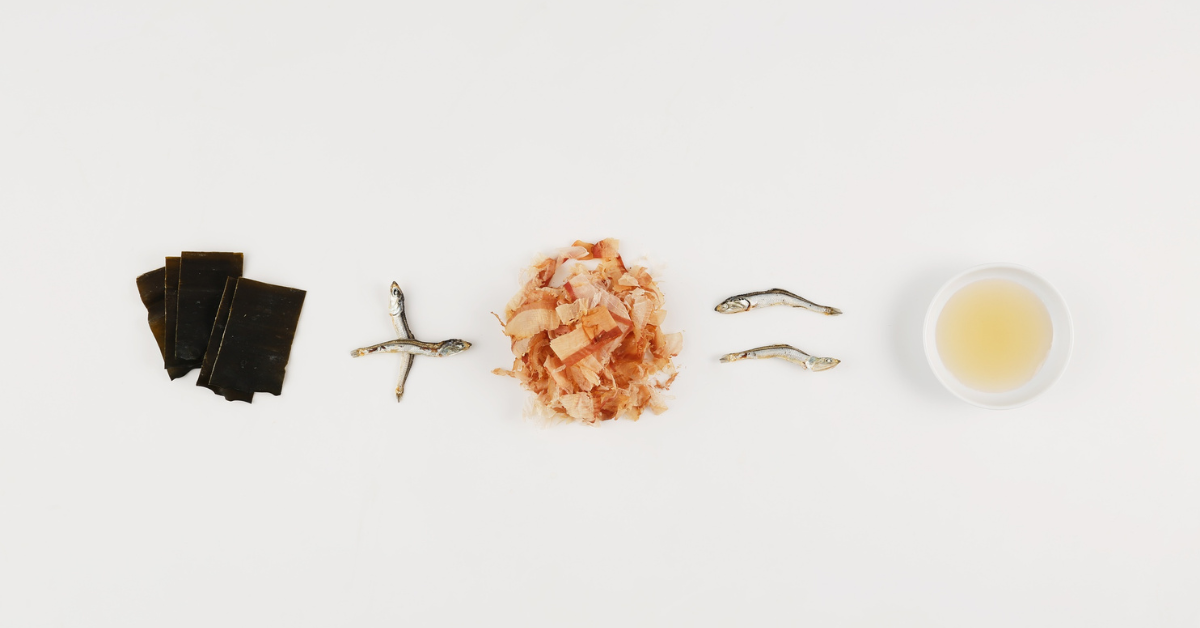

Umami was discovered in 1908 by Kikunae Ikeda, a Japanese chemist. He identified glutamic acid extracted from kombu (kelp) as its key component. Later, inosinic acid from dried bonito flakes and guanylic acid from dried shiitake mushrooms were also recognized as umami compounds. These components can act independently, but when combined, they create a synergistic effect that produces a stronger taste.

Representative Umami Compounds

| Umami Compound | Main Food Sources | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Glutamic acid | Kombu, tomatoes, cheese | Common in vegetables and seaweed |

| Inosinic acid | Bonito flakes, meat, fish | Found in animal-based foods |

| Guanylic acid | Dried shiitake, mushrooms | Abundant in dried or fermented foods |

Such compounds are present in everyday ingredients. For example, Italian tomato sauce contains glutamic acid, and when combined with meat rich in inosinic acid, it creates a harmony similar to Japanese dashi. Thus, umami is not unique to Japan but a universal sensory experience in global cuisines.

The Role of Umami in Japan

Japanese cuisine has developed by making full use of umami. Dashi, made from kombu and bonito flakes, is the basis of Japanese cooking, providing dishes with a subtle depth. This is not about adding more salt or oil but rather bringing out the natural flavors of ingredients.

Examples of Umami in Japanese Dishes

| Dish | Umami Components Used | Flavor Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Miso soup | Kombu’s glutamic acid + bonito’s inosinic acid | Balanced and deep flavor |

| Nimono (simmered dishes) | Sweetness of vegetables + inosinic acid from meat or fish | Mild and layered taste |

| Shojin cuisine (Buddhist vegetarian) | Kombu + dried shiitake | Rich flavor without animal products |

In this way, umami is positioned in Japan as “the taste that harmonizes ingredients.”

The Global Spread of Umami

Although once thought to be a uniquely Japanese concept, umami was officially recognized in 1985 at an international symposium in Hawaii as the “fifth basic taste.” Scientific research confirmed that receptors on the tongue can detect umami, and today, it is widely accepted in cuisines around the world.

Umami in World Cuisines

| Country/Region | Representative Ingredients or Dishes | Umami Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | Tomato sauce, Parmesan cheese | Glutamic acid |

| France | Bouillon, aged cheese | Glutamic acid + inosinic acid |

| China | Dried scallop soup, soy sauce | Glutamic acid + nucleotides |

| Korea | Kimchi, dried shrimp | Glutamic acid + fermentation compounds |

Thus, umami is not limited to Japan but a shared taste across human cultures worldwide.

How We Perceive Umami

The human tongue has taste buds with receptors that detect umami compounds. When glutamic acid or inosinic acid touches the tongue, signals are sent to the brain, where the taste is recognized as pleasant and savory.

Effects of Umami

| Effect | Description |

|---|---|

| Appetite stimulation | Enhances the desire to eat |

| Salt reduction benefit | Makes food satisfying even with less salt |

| Digestive support | Promotes gastric juice secretion for smoother digestion |

For these reasons, umami plays an important role in health-conscious cooking.

Umami and Cultural Background

In Japan, umami is not merely a taste but a cultural value. In tea kaiseki or Kyoto cuisine, chefs highlight delicate flavors by using dashi, conveying the natural beauty of the seasons and the essence of ingredients.

In modern Japan, foreign dishes such as ramen and curry also incorporate the concept of umami. Pork bone broth and caramelized onions are rich in umami, and the evolution of Japan’s diverse food culture is always supported by umami.

Conclusion

Umami is the core of Japanese food culture, yet it is now recognized as a global basic taste. Although discovered from Japanese ingredients such as kombu and bonito flakes, it naturally exists in cuisines from Italy to China.

For foreigners, understanding umami is not only the first step to enjoying Japanese cuisine more deeply, but also a way to discover the common threads that connect food cultures around the world.